Can the petro-rich subalten sheikh speak? How orientalism distracted from critiquing state power during the world cup

Part 1: The Human Rights Discourse during the Qatar World Cup

Seemingly nothing could contain my excitement waiting for the 2022 World Cup opening ceremony. I, along with my other Qatari countreymen, have waited for this moment for more than a decade. But then the universe, which in this case was the BBC, decided to schedule a seminar. The screen cut to a panel of talking heads explaining my country to me, going on about human rights, migrant workers, stadiums, gay people, the familiar reel of statistics with grayscale B-roll.

I am without hedging, pro-human rights (I must, nevertheless, hedge that the phrase needs to be properly cashed out). I want the pressure. I want the guardianship rules interrogated and the old kefala logics retired and not in name only. Part of me felt glad that some of the exploitations in my country done under the name of capitalism and nation were receiving global attention. I kept saying to myself that the substance is right. The kefala system extracted too much from people who had too little and that persecuting anyone for their consented, harmless adult sex acts is indefensible.

Then the broadcast kept going and going and the feeling shifted. The way “human rights abuses” was chanted. The confident flattening of an entire region into a single lecture slide, the exotic villain placed helpfully centre stage so the West could perform judge and jury without ever glancing at its own reflection. The critique I agree with on paper started to smell like theatre. My country was presented mainly as a prop of an Eastern barbarism that still maintains a medieval practice of indentured slavery and the repression of latent sexual identities which the civilised West liberated. The coverage spoke to an audience that already agreed, a monologue about a projected Other instead of a dialogue. Which means it was never going to persuade those who most needed persuading, and it was never going to reach those of us sitting in the uneasy middle space, both proud and critical, both attached and angry. It certainly was not going to move anyone with actual power, because people with power do not respond to televised shaming, so much as to costs, coalitions and stories that alter what their supporters think is respectable. It’s the rhetorical equivalent of posting a black square on Instagram and calling it activism. The subtext was that of a hierarchy of civilised versus backward, the same old Orientalism that’s painted this region as a project for Western salvation since the 19th century.

When the final whistle blew, the moral weather changed overnight. One moment the feed was full of think-pieces and grave voices, the next moment we were back to transfer rumours and compilation videos of stepovers set to nostalgic music. The brief vacation to the east wing of the Empire of Concern was over. #Humanrights was no longer trending on twitter. People like me, who live with the consequences long after the cameras pack away their cords, were left wondering who that performance had actually been for.

None of this means human rights language is useless, but the way it travels often strips it of voltage. I wrote elsewhere (somewhere) about the rationalist tone that floats above lived life. The declarative “X is a human right” feels clean to say, but it rarely converts the unconvinced. If you wanted to persuade my uncle who still thinks kefala is “basically fine if enforced properly” or that it is legitimate to prevent ‘absconding’, you would have to work differently. You would sit with a migrant and let him describe the debt he carried before he even boarded the plane, or the way his passport lived in someone else’s drawer for two years, and you would let my uncle hear how small a person can feel when their name is present only as a file number. That kind of rhetoric is slow and local.

British broadcasters, on that night, addressed a Britain that already nodded along. I nodded too. I nodded and still felt spoken over. That split feeling stayed with me, that I agreed with the claims and mistrusted the staging, I wanted reform and wanted a football match, I felt indicted and condescended to at once. Maybe that is the immigrant-at-home and citizen-abroad experience in miniature, or maybe it is just what happens when a global event turns your backyard into someone else’s lesson plan.

Was it a Clash of Civilisations?

The rhetoric did far worse than not persuade anyone who needed convincing. The larger rhetoric around human rights seemed to have triggered an effectively anti-human rights reaction from many Qataris, if only out of spite. A moral panic among Qataris ensued about the infiltration of sexual minorities into Qatar, as if none already existed. Suddenly, rainbows were public enemy number one, feared as if they were some sort of demonic gateway for an invasion of gay zombies. And charges of orientalism, western exceptionalism, cultural imperialism and hypocrisy were the main rhetorical weapons in Qatar’s toolkit. The discourse descended into a pantomime of East vs. West, each side essentialising the other.

And then, low and behold, I saw it out in the distance. Samuel Huntington’s ghost popped up on the screen screaming: ‘BEHOLD! the Clash of Civilizations I had predicted decades ago!’ Okay… that didn’t actually happen, but his theory was suddenly trending again, and not in a good way. Huntington talked about a clash of monolithic entities, ‘Islam vs the West’; “The great divisions among human kind and the dominating source of conflict,” he wrote, “will be cultural . . . the clash of civilizations will dominate global politics. The fault lines between civilizations will be the battle lines of the future.”

Superficially, Huntington seemed vindicated. I watched as scenes of Qatari imams went on evangelising rampages handing out flyers to foreign football fans, Muslims in Rohingya lifting portraits of MBS and cheering for Saudi Arabia’s national team, tournament officials confiscating rainbow flags, Palestine armbands being turned into anti-LGBT symbols, a talk of sports teams as colonisers and colonised, the German national team gesturing protests about LGBT persecution. Islam as the last standing unyielding “Other”, the West as missionary of progress, both trapped in a feedback loop of mutual provocation. In none of this did the the lived realities of migrant workers, women, and queers rendered visible, they were simply casualties of a rhetorical war waged between two hegemonic narratives.

Incitement to Discourse

As I watched the madness unfold, I couldn’t help but think of these totalising, grand stories that began circulating in the 90’s about such supposed civilisational clashes, about uncommunicating communities and moral and cultural inbcommensurablites and so on. Whether or not we're starring in some cosmic civilisational showdown (I'm leaning towards "not"), there's no denying our world is a patchwork of different historically conditioned perspectives. But the World Cup laid bare not exactly a clash of civilisations, perhaps a crisis of translation, mainly as a result of a failure to set the conditions for a fruitful social negotiation about our ‘global village’ (and the global events that are held within it).

It is helpful here to focus for a moment on the moral hysteria that took place during the 2022 World Cup over alleged abuses of ‘LGBT people’ who desire to be recognised, and ultimately ‘liberated’.(1) The problem with this framing from the frame of reference of ‘us’ Qataris watching, is that when Western NGOs and broadcasters demand that Qatar ‘reform’ in this way, they smuggle in a teleology of progress that crowns a specific vocabulary, that of the modern West, as the measure of civilisational height. As Joseph Massad had argued decades ago, the debate that follows rarely concerns desire or conduct in any concrete sense. It concerns the epistemology of sex, the taxonomies that classify practices and persons, and the scope of identity in relation to nation, culture and religion. And it is invariably met with predictable defiance that hardens into a paranoia.

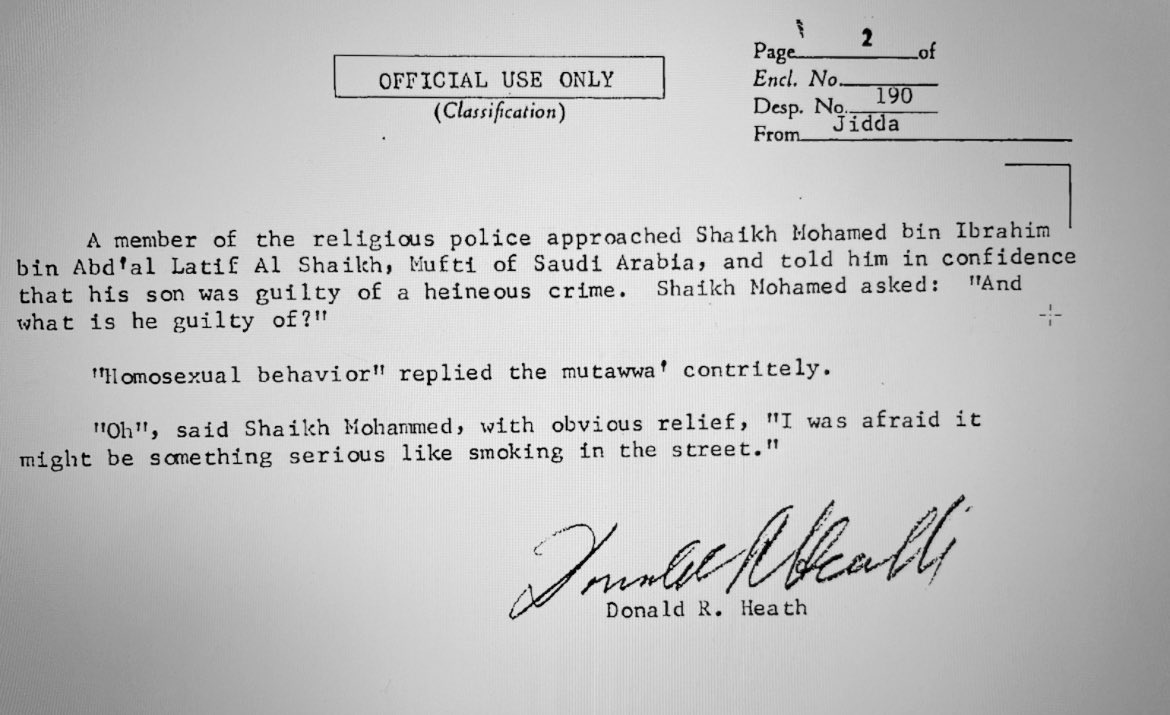

For a long time, same-sex relations in the Arab world rarely peneterated official discourse, tolerated in private, discussed obliquely in schools and social circles, structured by practice rather than identity. When the US set up ARAMCO in Saudi Arabia, they had a great deal of interest in maintaing ‘order’ in the region. This telegram from the American Ambassador Donald Heath (1958-1961) is quite indicative, in which he writes that a religious police officer came to the Kingdom’s Mufti Ibn Ibrahim and said to him: Your son has committed a heinous crime.

The Mufti: What did he do?

The Muhtasib: Sodomy!

The Mufti replied: Oh, I thought it was something serious like smoking in the street.

Perhaps the most significant and prominent cultural product associated with homosexual acts in Saudi Arabia is a specific type of music genre that is popular among the youth called “Al-Kasrat” songs, often played to folk-style music. In these songs, the artist speaks openly and directly about their homosexual relationships, varying in their explicitness. Here a poet tells the story of his suffering with the beloved who studies with him at the same school. He says: A story happened to me in a school with someone, by God, he wore me out. O People, I don’t know what his deal is. He cuffed my heart and tortured me. You tortured my heart during al-fusha, our recess. Oh beauty, you with the blue look. The problem is he’s a head-turner. So many are crazy about him. I show up every day for his sake. I didn’t skip a single day. One glance from his eyes is enough for me, and I end up burdened because of him. I just roam the asyāb, the hallways, going to and from his classroom. I just keep racking up my absences, and all I want is that one look. When Wednesday comes, sadness creeps into my heart. Thursday and Friday feel like a whole week. I toss like I’m on burning coals.

Obviously this is not a European regime of bourgeois monogamous marriage. But unless we accept that sexual categories are a-historic, pre-discursive, universal categories and not historically conditioned constructs, then one wonders why it must it be such a regime? None of my classmates identified as a particular sexual category, and I do not for a moment believe that they were simply conceptually impoverished or confused in some way; that they did not ‘have’ the conceptual/linguistic toolkit to express this supposedly latent need for recognition of a sexual identity because the particular repressive cultural milieu in which they live does not offer any terms with which to lexicalise the concept in question. The identity practice itself had little uptake; there was no live inferential role that licensed a standing self-ascription such as ‘gay’. On the view I accept, to ‘have’ a concept is to participate competently in a public language-game where that concept is governed by norms of use, not to possess a private mental token. If so, exporting a ready-made inferential role is a form of conceptual imperialism unless it emerges through translation, co-authoring and local uptake. Campaigns that claim to ‘defend’ people everywhere who are presumed to already ‘be’ those identities produce, in the process, ‘homosexuals’ as an identity where earlier there were practices without identity, and trigger new forms of surveillance, law and media attention that reframe those practices as a public problem.

The western educated liberal-minded human rights activist likes to think that just like children or laypersons might not ‘have’ a concept in, say, theoretical physics, many Arabs lack concepts of ‘gayness’ as ontologically construed by them. The branch of people would call them ‘closeted’, where the closet trope functions as a source of possible certain knowledge, in which, behind its closed door, lies a truth waiting to be revealed—the old enlightenment binary of knowledge/ignorance, so that ‘coming out’ requires adopting specific discursive sexual and gender categories and speaking in particular ways about one’s erotic experiences, relations and desires. So we have the patronising idea that the truths the West reveals are unknown to the individuals themselves. That these men and women may simply practice sex acts on others and not ‘be’ gay (not ‘have’ such an identification or self-declare it) is never interrogated by Western audiences.

Must the entire world adopt the epistemological and ontological notions of sex acts that the West promulgates, which is now ensconced ipso facto into the prevailing global discourse on ‘human rights’? Though colonial encounter and imported capital and its perpetuation of what it describes as ‘modernisation’ projects certainly did reshape norms and sensibilities in the Arab world considerable. The average Arab today would be almost wholly unrecognisable to their great-grandparent. Parts of this project has had terrible effects much earlier on general inclusive Arab conceptions of sex morality, where much of nineteenth-century colonial projects assimilated Islamic jurisprudential permissiveness on contraception and, at times, abortion, to Victorian Christian strictures.^1 However, they did not yet install a universal European heterosexual regime on all Arabs. Uptake clustered among elites and a Westernised middle stratum, the milieu from which the 2022 World Cup media sometimes drew its most fluent interlocutors. Some men in these circles have adopted Western identity labels, often as part of a broader package of aspirational Western styles but they remain a small minority when set against the many men who engage in same-sex relations without identifying as ‘gay’ or seeking gay politics.

The World Cup cycle of moral outrage in Doha thus looked like a familiar pedagogy, a missionary script that ranks cultures and demands conversion to a particular taxonomy of sex. I am not, here, drawining a story of victim and victimiser, not am I claiming to speak for the ‘subaltern’ petro-rich Qataris. Qataris specifically as a class are the richest population in the world per capita, the large benefactors of global capitalism and have undoubtedly perpetuated this system. But the very base of Qatari society has been formed at a historical moment of mid 20th century anti-imperial memory and the storm of Pan-Arab media ecologies such as The Voice of the Arabs, and today they watch as representation of Arab and Muslim cultures predominate in the more ‘enlightened’ Euro-American media which still mirror the representations of the 19th century classical Orientalists in portraying them as barbarians; terrorists and fanatics.

The effect of the incitement to discourse is therefore far more constrictive than it is liberatory. As mentioned, same-sex relations in the Arab world had largely remained outside state and journalistic discourse, and many practitioners preferred that discretion. The World Cup cycle of indignation incited a new, punitive conversation that framed Western media and human-rights NGOs as antagonists. As publicity intensified, enforcement shifted toward identity and visibility rather than private conduct, where the targets became those who name themselves ‘gay’ and seek collective presence in social or public settings. Private acts are difficult to police and often managed through silence, but identity, once declared, is readily legible and sanctionable. The incitement thus installed an ontology of ‘gayness’ within the emergent discourse, compressing prior ambiguities into a binary in which one either endorses or opposes ‘gay rights’, while the presuppositions of that framework go unexamined. Within the modern anticolonial nationalism, and within an Islamism that seeks technological modernity while preserving notions of cultural or religious authenticity, the campaign read as encroachment. The reliance of of this discourse on the institutions associated with U.S. 21st century imperialist power—the State Department, Congress, U.S.-based NGOs and media—only confirmed that reading. Young Qataris’ adoption of Palestinian armbands in response to European team protests against FIFA’s ban on LGBT symbols, alongside silence and complicity in Israeli apartheid, ethnic cleansing and mass violence, was an unsurprising rejoinder to selective Western empathy. The Palestinian cause has been, since its inception a little less than a century ago, the last remaining defining feature of ‘Arabism’ across continents, perhaps only behind Islam, and it is therefore predictably what the masses of Qataris reached for when sensing a threat of Western cultural imperialism, the same West that abets the violence against their Palestinian fellow. I recall coming across a thin paper booklit entitled ‘Qatar’s Shaykh speech on Independence 1971’ on my days scouring through the Durham University library archives. I was astonished to read that the speech begins and ends with an explicit solidarity with Palestine as a declaration constitutive of Qatari identity from its inception (even though the Gulf shaykhs mostly wished to retain British imperialism at home). The upshot is that the negativity of the reaction does not matter as much as the fact of reaction entrenches the identity grid. By any practical measure, this sequence narrowed rather than expanded sexual freedom.

Now, on the flip side, the counter-discourse that emerged in Arab circles during the World Cup was Islamist and conservative, presented as an authentic Islamic denunciation of Western ‘cultural imperialism’, even when their idioms on purity, pathology, family decline, medicalised deviance, echoes US Christian-Right talk almost verbatim. Once sexuality is made a public identity question, these actors step forward with a civilizational narrative keyed to disease and moral panic. There is therefore a political symmetry where both the LGBT campaigns and the conservative nationalists and Islamists all end up complicit with Euro-American imperial knowledge, fighting one another in public, but sharing premises about identity, visibility and the civilisational stakes of sex, which is why their rhetoric can look interchangeable.

On a more general tangential point, I keep seeing this mimicry among my friends and cousins (most of us Western-educated). They repeat American conservative culture-war lines almost verbatim while praising Islamic and Arab authenticity as a bulwark against Westernisation. Joe Rogan and the likes provide the cultural idioms decrying transgender athletes, immigration, radical feminists and so on, but the local referents rarely fit. Popular media platforms gravity pushes English-language, high-conflict content into our feeds, so that high-charged notion of ‘woke’, ‘race’, ‘trans’ become into floating signifiers that stick to mismatched institutions. Our parents did not inhabit this incited field of discourse, but we do, courtesy of recommendation systems that make the West’s culture wars feel native. In both cases, it is a glocal culture-war market that we, the Global South population, have the impression of ‘picking’ from.

Western NGOs were right to spotlight migrant abuse in the Gulf. They were wrong to provincialise it as a uniquely exceptional kind of barbarism inherent to the region. To the state and employers, the migrant worker appears as a contract-bound economic actor, a temporary guest in a relation of supposed mutual benefit. In the migrants’ own account one may hear a different story of the ambitions that carried him from Dhaka to Doha, the kinship networks that sustain him, and the humiliations registered as ruptures of dignity rather than as an abstract ‘rights’ violation. But the World Cup discourse was suspiciously absent in reference to structural issues of global capitalism, of recruitment debt in sending countries, sponsorship rules and brokerage chains in the Gulf, document capture and wage differentials entrenched by global labour markets. The World Cup Western conversation largely ignored this structure because it reveals the darkness thats exists in their own back gardens. Turning the lens inward would mean examining the political economies that make exploitation rational for firms and inescapable for workers. This does not absolve anyone and the Kefala system is not a mere ‘cultural difference’; it is a harm-producing labour law that could and should be dismantled in Qatar and elsewhere and replaced with enforceable rights: zero-fee recruitment, portability of visas, freedom to change employer, restitution of back pay and serious penalties for passport confiscation.

This has been the main concern of this entry: rejecting the export of epistemic and identity categories as instruments of reform (for example, visibility politics that makes ‘gay’ a required self-ascription), and rejecting broadcast shaming that stages Western moral authority. That package provoked sovereignty theatre and tighter repression during the 2022 World Cup. In what follows, I examine the presuppositions we, as human-rights advocates, bring to cross-cultural engagement. I endorse a normative universalism about harms (coercion, degradation, avoidable injury) without claiming stance-independent moral facts. Keep universal verdicts; drop metaphysical grounding; pursue change through translation, coalition, and local uptake. We can oppose the imposition of classificatory schemas as a precondition for reform and still hold that some harms are wrong wherever they occur, not because a metaphysical substrate makes them so, but because these are the standards we avow. Their articulation should emerge from locally authored concepts and idioms, and from coalitions and institutions capable of carrying them.

Part 2: Cultural Relativism and Universalism

Meaningful cross-cultural communication cannot thrive in the stuffy confines of the traditionalists' cultural isolationism on the one hand, and UNESCO's "windowless" cultural relativism on the other hand (as cheekily dubbed by anthropologist Clifford Geertz, where human communities are in his words “semantic monads”). To speak of cultural boundaries as fixed, impermeable entities is to indulge in a fiction. Cultures are palimpsests, they are always borrowing and fusing ideas, food, fashion, and so on. One may go so far as saying, with Geertz, that other cultures are constitutive of one another, that routes supervene on roots. Static “natives”, anchored in place and untouched by outside contact have probably never existed outside the misguided writings of meandering 19th century European anthropologists.

And so in that sense, in the words of philosopher Paul Feyerabend, “potentially, every culture is all cultures.” At the boundaries we find ambiguity and plurality; people juggle repertoires. I balance a Qatari socialisation with a Western education (moving in and out of different cultural prototypes, mixing and matching), and many gay and feminist Muslims navigate faith, gender, and sexuality in the same register. People tolerate such ambiguity, and they settle apparent contradictions by simply dissolving them. So if we accept that boundaries are what they are as chimeras, we can start treating all cultural practices as our own practice. Torture is an offence wherever it occurs, not a mysterious “other cultural” act, and interventions should begin with the local voices that already condemn it. This calls for a humility alien to both missionary and nativist postures; the Muslim who also performs same sex relations and the feminist imam are both intelligible figures. We defend these prohibitions from within our standards, without claiming a view from nowhere, and we act only after sustained contact with the populations directly involved.

The promise of such an approach is translation not consensus, it is the arduous, imperfect work of finding equivalences across difference. When a Qatari woman demands autonomy from male guardianship, she may couch her plea in the language of Islamic equity rather than liberal feminism. But to dismiss her demand because it invokes hadith rather than Hobbes is to privilege form over substance. Conversely, when Western activists invoke “LGBTQ+ rights” in Doha they simultaneously conflate liberation with the universalisation of Western identity categories, to make them casualties of a “rescue narrative” that serves the activist’s savior complex more than the actual needs of the oppressed, in just another empire singing “We Are the World” while the marginalised write their anthems in the margins. In short, cultures, in the final analysis, are verbs, not nouns. They are performed, not inherited. They are remade daily in the choices of individual performances that have no qualms with apparent contradictions of their moment, as contradictions imply cultures as reified entities with boundaries.

Universalism vs. Relativism

The debate that unfolded during the World Cup existed in a spectrum where on one end we find Western journalists and activists who invoke universal human rights while sometimes smuggling in these are metaphysical truths. On the other end of the spectrum we find ‘subaltern’ petro-rich Qataris, PR-savvy social media firms, postcolonial professors, and FIFA. The former accuses the latter of of cultural imperialism, Western exceptionalism and hypocrisy. Some go on to then weaponise outdated liberal values like ‘non-judgment’ to legitimate harmful practices. When it suits them, they’ll also cosy up to normative cultural relativism—a prescription for tolerating the moral practices of other cultures no matter how much they might disagree with them. This was exemplified by the FIFA president’s pre-tournament address to the press when he claimed that the West is being hypocritical when criticising Qatar for the conditions it puts migrant workers and exclaims that “for what we Europeans have been doing for 3,000 years around the world, we should be apologising for the next 3,000 years before starting to give moral lessons to people”. He was right about Western hypocrisy, wrong that hypocrisy licenses toleration of current abuses.

Right above Culture (normative universalism):

On the one hand, human rights advocates, in wanting to make universal prescriptions and “ground” (i.e., defend the philosophical position behind) normative universalism and a universal procedural justice system, they (in my view, mistakenly) affirm metaethical realism. The latter is the view that there are moral facts (e.g. human rights) that are not made true by anyone’s stances. In the context of human rights, that there are these ‘natural’ moral obligations which we might call ‘rights’ that come about simply in virtue of being a featherless biped, and these moral obligations are made true independent of anything anyone thinks about them—are not made the case by our perspectives.

Or to put it in terms of normative ‘reasons’, all individuals are universally conferred with minimum moral obligations that cannot be trampled by the interests of their culture or group. The justification for these moral obligations is that they are backed up by stance-independent normative reasons. So to say that there are human rights against torturing babies for fun is to say that you have a normative reason to not torture babies for fun. This relies on the idea that there are reasons for action independent of our desires, attitudes, beliefs, choices etc., as in you have a reason to not spend your life counting spades of grass whether you like doing so or not. (See my critique of this view here).

Right to Culture (normative relativism):

On the other hand, human rights advocates of whom Claud Levi-Strauss had approvingly called ‘UNESCO cosmopolitanists’ affirm a naive normative cultural relativism, a prescriptive position popularly held among early 20th century anthropologists which holds that we must tolerate the moral practices of different cultures (principles of non-interference and non-judgment). This is exemplified in UNESCO’s Our Creative Diversity 1995 report which reiterates the tweet above in saying that cultures deserve to be treated “with respect” (as if there’s clearly bounded ‘cultures’ that are not further divisible into contradictory subcultures), and frames the issue not as ‘human rights vs culture’ but as ‘a human right to culture’, and then equivocates on the word ‘culture’ between ‘a way of life’ and ‘an aesthetic work’. This ‘respect our culture’ rhetoric is exactly the type of rhetoric which the Saudi government in its treatment of women, nationalists in their demand for stricter border controls, the genital mutilators in Somalia, the Islamic State and ethnocentrists all over the world can all happily rejoice with.

Taken together, the human rights advocates express the following propositions:

We hold that human rights norms are universally applicable, and they are ‘grounded’ by stance-independent moral reasons.

We ought not judge the moral norms of other cultures.

Can’t Have Your Cake and Eat it Too

Seting aside the metaethical point (i.e., the ‘grounding’ part), clearly there is a contradiction here; human rights advocates are endorsing normative universalism and normative relativism simultaneously. That is, there are claiming that we ought to tolerate other individuals or groups that act against human rights because such an act is a cultural act, and that we ought not tolerate individuals or groups that act against human rights irrespective of culture. Human rights advocates are thus framed as moral schizophrenics and condemned as hypocrites for making two contradicting normative claims. They can’t have their cake and eat it too; they can either affirm normative universalism or normative relativism, buy not both at once.

I suggest that human rights advocates jettison normative cultural relativism as there is no good reason to uphold a position which precludes a capacity of moral indignation and contempt—or interference if the situation so needs. It is antithetical to a ‘human rights’ project.

Human rights, by their nature, involve universal prescriptive norms that are insensitive to the cultural standards of the actant individual or group. If Siberian Shamans had historically developed a ritual to kill odd-ordered born babies for fun, then presumably, the human rights project aims to in some sense interfere with that ritual. After all, the Universal Declaration explicitly confers rights to individuals (the odd-order babies), not groups (the Shamans). And all human rights start off with some universal normative judgment, such as ‘no distinction shall be made on the basis of ...etc.’

Or consider a real historical example: the practices of the early Ache tribe of Paraguay as described in 1972 by anthropologist Pierre Clastres in his Chronicle of the Guayaki Indians. The tribe was reported by Pierre to practice cannibalism, kill elderly people with Alzheimer because they are thought to have harboured dangerous vengeful spirits, have pre-pubertal sex, abandon their aged, beat menarcheal girls with tapir penises and cut them with broken glass, and what’s more, they held ‘clubfights’ where men would fight sometimes to the death, similar to Roman gladiator contests. It would be rather odd to say that the human rights project was intended to protect the ‘right to culture’ of the Ache tribal men rather than protecting the menarcheal girls’ ‘right above culture’, viz. their right from an abusive cultural practice. The retort by the men that such a practice is a “cultural” practice to which they have the right to will fly in the face of the girls’ rights above such culture.

Human Rights Advocates Should Not “Ground” Normative Universalism

As discussed earlier, human rights advocate often wish to “ground” the normative universalism which the human rights culture is based on with metaethical realism, that is, by saying that they are backed up by stance-independent moral facts that apply to everyone, at all times, everywhere and independent of any perspectives or cultures. I suggest human rights advocates give up on metaethical moral realism for they would otherwise be opening themselves up to accusations of smuggling in their own social practices into something ineluctable and transcendental that is intrinsic to all humans and then calling it ‘true independent of any stances’. I suggest that human rights advocates abandon the attempt to “ground” universalism altogether and instead endorse a pragmatist approach to human rights without ever eluding to the metaphysical nature of such rights.

A better reformulation of the human rights advocates’ position would thus be the total inversion of the characterisation above, i.e., by affirming metaethical cultural relativism (with a deflationary account of truth) across the board accompanied by a normative universalism (while allowing a plurality of culturally-specific values; such as, for example, the right to own a goat or the right to die among family, etc.):

We hold that the cluster of moral norms we call ‘human rights’ are true and ought to be prescribed universally. We also affirm that we ought to not tolerate cultures and individuals that act in opposition to those norms.

We do not wish to ‘ground’ the truth of the human rights norms, nor the subsequent normative claims on universal prescription and non-tolerance. Any attempt to do so will be circular.

Instead, we acknowledge that human rights norms (and the subsequent normative claims) are true or false relative to standards. When indexed to our standards as human rights advocates, they are true. When indexed to the standards of Medieval Christians, they are mostly false. Yet, we are none the worse for that.

The fear often expressed when endorsing such metaethical relativism is a common rhetorical sleight of hand which equivocates metaethical considerations (‘the truth of human rights is relative to standards’) with normative considerations (‘we ought not judge cultures with different standards’). But metaethical relativism does not logically entail any normative consequences (the clue is in the name). Acknowledging human rights as stance-dependent norms that are indexed to our standards doesn’t mean that we are precluded from normatively judging practices that contravene them.

To use an analogy, we acknowledge food or music taste as being relative to preferences but that doesn’t impede our ability of having strong food or music preferences or in judging, or even going to war against, people with contravening preferences if we are so inclined. Remember, the comparison between human rights and food/music is their meta-normative characteristics, and specifically NOT how important they are or what ought be done about them or how much they should be imposed on others—those are all normative, not metanormative, stances. It just so happens that a feature of music/food preferences is that they are not typically imposed on others and people do not usually ‘judge’ others for holding different music and taste preference. But, in principle, someone can be a meta-normative anti-realist about music/taste/aesthetics etc. and simultaneously hold a normative stance that their preferences ought be imposed on everyone. This is the view I advocate for with respect to human rights. We can be anti-realist about human rights and simultaneously hold a normative stance that human rights are extremely important and prefer that everyone else follows those norms.

Unfortunately, many human rights activists think that in order to be rhetorically effective they must adopt, even if implicitly, moral realism as a metaethical stance, in which moral sentences are ‘made true’ by the intrinsic nature of the world and not by our evaluative standards.2 They think that they must insist that rules for action really matter only if those rules were independent from us, in which case they will only ‘psuedomatter’, and that this will win them more rhetorical points among unconvinced populations. They think that maintaining a metaethical relativism or constructivism will make those rules arbitrary and deprive them from their necessary ‘oomph’.

Philosopher Richard Rorty highlights this psychological dilemma within liberals who use rationalist rhetoric of the Enlightenment to justify their liberal convictions:

These liberals hold on to the Enlightenment notion that there is something called a common human nature, a metaphysical substrate in which things called “rights” are embedded, and that this substrate takes moral precedence over all merely “cultural” superstructures. Preserving this idea produces self-referential paradox as soon as liberals begin to ask themselves whether their belief in such a substrate is itself a cultural bias. Liberals who are both connoisseurs of diversity and Enlightenment rationalists cannot get out of this bind. Their rationalism commits them to making sense of the distinction between rational judgment and cultural bias. Their liberalism forces them to call any doubts about human equality a result of such irrational bias. Yet their connoisseurship forces them to realize that most of the globe’s inhabitants simply do not believe in human equality, that such a belief is a Western eccentricity. Since they think it would be shockingly ethnocentric to say “So what? We Western liberals do believe in it, and so much the better for us,” they are stuck.

Rorty’s advice follows the line of thought I’m getting at, which is to say ‘yes, our cultural practices are not universally held nor are they etched into the fabrics of the cosmos, but so what?’ There is no principled distinction between cultural bias and rational judgment if we acknowledge that we cannot reach out from under our cultural practices and institutions into a God’s eye view. We cannot, in other words, shed our frame of reference temporarily and rise up into a neutral, omniscient point of view and then start to compare all frames of references. The terms we fall back on are, after all, always self-consciously ethnocentric: ‘as a… Qatari’.., ‘Marxist’, ‘Liberal’, ‘Muslim’, ‘anthropologist’ I think thus and so. And so Rorty urges human rights advocates “to take with full seriousness the fact that the ideals of procedural justice and human equality are parochial, recent, eccentric cultural developments, and then to recognize that this does not mean they are any the less worth fighting for . . . [and] the best hope of the species”. In this construal of what Rorty calls ‘liberal ironism’, Rorty is echoing the liberalism philosopher Isaiah Berlin when he ended his famous essay Two Concepts of Liberty by saying that his ideal political community is one that realises ‘the relative validity of [its] convictions and yet stand for them unflinchingly’.

-

I am not claiming here that there was zero stigma or zero punishment prior. Laws that were unevenly enforced existed. But the point is that public state and media focus was relatively limited and episodic, and that identity-based persecution intensified once the campaign made ‘homosexuals’ a public object of debate. Unenforced laws begun to br enforced and even where there were no specific provisions saw police harassment once the nationalist–Islamist backlash kicked in. The so-called homosexual merely saw more exposure to policing. ↩

-

In technical jargon, there are antecedently existing “truth-makers” tracked by some truth-tracking faculty. Usually the truth-makers are how human beings are qua humans, i.e. some alleged intrinsic “human nature” that’s truth-tracked by “human reason”. ↩

Home

Home About

About Entries

Entries Chat

Chat Kool Webpages

Kool Webpages Guestbook

Guestbook Kool Books

Kool Books Truth Table

Truth Table Contact

Contact