What is Truth Part 1: ‘What is a Woman?’ Is a Bad Question

The dogma of representationalism in Philosophy, its spillover into the Culture Wars, and how to better approach ‘what is X?’ questions.

“God is not known, he is not understood, he is used—sometimes as meat-purveyor, sometimes as moral support, sometimes as friend, sometime as an object of love. If he proves himself useful, the religious consciousness can ask no more than that. Does God really exist? How does he exist? What is he? are so many irrelevant questions. Not God, but life, more life, a larger, richer, more satisfying life, is, in the last analysis, the end of religion.”

—James Henry Leuba

Many philosophical and ideological debates often hinge on disagreements over what “exists” or what is “real”, in an ontological sense. This is certainly the case in debates between atheists and theists. Atheists may argue that belief in God causes greater suffering, but the theists see this as missing the point; God does exist, God and souls are real entities. While on the other hand, so-called “nominal theists” and social gospel theologians may argue religious belief makes them happy, to which atheists may retort that they’re missing the point; God doesn’t exist. There is no such entity.

What is shared between both camps is the adherence to what Hegel called “onto-theology”; the obsession over metaphysics, over “grounding” their arguments on what is ontologically ‘out there’. This is an ancient Platonic need to prostrate against something non-human and towards what is really anyway there, irrespective of questions of human happiness and well-being. Yet we find that, in the final analysis, the only relevant question in the dispute, the one that we actually engage with in practice, is the question of how we may best carve out our linguistic and social practices with respect to religion in a way that contributes to our goals and interests. The reflection on the ontological status of religious entities or the will of a purported deity only comes to the fore in hindsight, after questions about whether talk about such entities serve relevant social and normative goals, such as the goal of human brotherhood and love or hope and meaning .

In a similar vein, the question of whether gender categories are ‘real’ in an ontological sense is much less pertinent than the question of how we can best refine our linguistic practices when we talk about gender. It is often said, for example, that we should use language that affirms a person’s identity and experiences, such as saying “assigned female at birth (AFAB)” or “assigned male at birth (AMAB)” rather than “biologically female/male”, that we should refer to people by their preferred pronouns, update public signage to use more inclusive language, and to stop using the concepts “tranny” and “she-male”. The idea is to lessen the chances that questions like “What was their biological sex?” or “Is this person ‘really’ a man or a woman?” will be seen as relevant. The focus here is about how we may best refine our linguistic practices when we talk about gender, and hopefully come to the resolve that we ought to do so in a way such that fewer and fewer kids will grow up being asked, ‘Why do you act the way you do when you’re supposed to be something else?’ and fewer and fewer of them will grow up severely distressed about the conflict between their identities and their bodies, and about how their family and friends treats them, and be condemned for wanting to change that.

Critics counter this line of thought by saying, “But biology does matter; sex is real.” The rejoinder is: there certainly are biological markers between human populations associated with sex, but these markers do not, in themselves, correlate with any characteristics that give us good reasons to treat those individuals in a specific way as opposed to some other way. In medical contexts, understanding genetic and hormonal differences may be important, but not for most other contexts. So, the questions “Do these gendered categories exist in the way we traditionally thought?” and “Should we continue to talk of them in these ways?” are pretty much the same.

Unfortunately, however, onto-theology is still heavily part of our culture, with recent obsession over the metaphysics of gender overpopulating our thoughts. This brings us to… What is a woman? The question sparked endless debates and even political movements as gender identity and expression have become increasingly complex and fluid. While the conservative side of the debate leans on essentialist claims rooted in biological determinism, many progressives nevertheless indulge the question by attempting to define the essence of ‘womanhood’ in their own terms.

But again we’re asking the wrong question.

The question ‘what is a woman?’, like the question ‘does God exists?’, is poorly framed, not because it lacks an answer, but because it assumes a representationalist view of language and ontology. This Platonic grasp on our culture attempts to define gender categories based on pre-existing “natural kinds,” and assumes that language serves to accurately represent these kinds, so that those who wish to reform language are failing to track such representation.

If, however, we follow Wittgenstein’s use-conditional approach to language and meaning instead, we will free ourselves with the fixation over ontological categories and essentialist definitions and turn our gaze towards the more pressing normative and pragmatic concerns. Rather than trying to pin down the essence and metaphysics of gender, we would be asking how, above all else, can we maintain or reform parts of our linguistic practices so that more people can lead richer lives.

For all attempts to assert an authority higher than our social concerns - be it God, Truth, Reality, Biology, or Human Nature - are, in the end, disguised manoeuvres over such concerns. These asserted authorities are not, as their proponents hold them to be, language-independent or universal, but are products of past generations’ own social and linguistic practices. As these authorities don’t exist independently of human practices, they should not, therefore, be accorded a primacy that supersedes or negates their social origins. So again, the ultimate question is thus: ‘how can we use our linguistic and social practices to make the world better for us to live in?’, as opposed to the question of whether p or q really exists.

People who do appeal to a divine or metaphysically distinct authority in disputes about how to carve our linguistic practices often seem to have a clear idea of what this authority commands or desires. And yet, these commands and desires also just so happens to be closely aligned with their existing moral and social beliefs, which are, in turn, shaped by their specific cultural and societal context. What is being presented as a metaphysical mandate, in other words, often merely reflects whatever happens to be part of the linguistic norms the individual is socialised into in their respective linguistic community, and the sleight of hand of adding metaphysical weight to this norm, such as in claiming that it is part of “Human Nature” or corresponds to “Reality”, is nothing more than a table thumping exercise.

So going back to the ‘What is a woman’ question, the injunction I’m proposing demands prioritising normative considerations about how we ought to carve out our concepts with respect to gender, over pointless metaphysical investigations on its “essence”. The shift is particularly needed at a time where many media outlets are increasingly looking for ways to stratify society and assign blame for societal ills. Alarmingly, their attention is steadily shifting towards scapegoating the newest minority on the block—transgender individuals. Backed by pseudo-intellectual arguments, this scapegoating tactic uses quasi-fascistic strategies championed by neoconservative figures like Matt Walsh and Ben Shapiro on one side, and gender-critical feminists like J. K. Rowling on the other.

In the following sections I delve deep into and dismantle two related frameworks which I take to be influencing much of current transphobic rhetoric. The first is representationalism, the view that reality has an intrinsic nature which the task of language is to represent. And the second is essentialism, which holds that objects must have a set of properties that are necessary for their identity. They are both related because they both stem from foundationalism: the belief that the task of inquiry is to discover ahistorical and necessary foundations for our current cultural practices, ranging from the sciences to religion, ethics, and art.

Representaionalism

Many philosophical queries, largely inherited from 17th century epistemology and metaphysics, center on uncovering the inherent nature of things, or, as Derrida phrased it, “a full presence beyond the reach of play.” This search for hidden essences—which is taken as being important for its own sake—amounts to tedious questions over matters, such as:

“What is qualia?”

“What is Knowledge?”

“Are there really universals?”

“How do we know what we know?”

“Do we know p, or its mere appearance?”

“Is there a place of value in a world of fact?”

“Are there moral or epistemic facts independent of any stances?”

“Do these facts alone give us reasons for acting or believing?”

“How many grains make a heap?”

“Why is there something rather than nothing?”

“What is time?”

“Does God exist?”

“Do we have free will?”

The common issue with these questions isn’t that they lack answers, but that they are linguistically deceptive and poorly framed. Because of the way they grammatically appear, they seem expectant of an answer—when they shouldn’t be. All they do is merely mimick the syntactic structure of answerable questions such as “is there a cup in that cupboard?”.

Take, for example, the clearly ill-formed question, “Do chairs enjoy listening to Lady Gaga?” The question is perfectly grammatical coherent. But when taken in speech form, the question is semantically vacuous because it applies words and structures from our lived experiences to contexts where they have no meaningful application, and therefore just one more example of our tendency to treat all noun-like entities similarly.

Likewise, the classic “why is there something rather than nothing” assumes a grammatical form that invites an answer, but is mere gobbledygook because it has no application in that context. In everyday conversation we employ the term ‘why’ to ask for causes or reasons within a predefined system of understanding—typically within the boundaries of human experience. But when we ask ‘why’ about the totality of existence itself, we are misapplying the term ‘why’ in a way that strays from how the word functions in our language.

The allure of these philosophical investigations, as argued by Richard Rorty in ‘Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature’ (1979), stems from analytic philosophy’s dogmatic commitment to representationalism. Representationalism rests on three premises:

1. Reality has an intrinsic nature.

2. There is a medium that represents reality, thus bridging the ‘self’ and ‘reality’.

3. This act of representation is valuable for its own sake.

Traditionally, the mind has been perceived as such a medium. But due to the nebulous nature of consciousness, language emerged as a preferred medium with the analytic turn in philosophy, particularly following Gottlob Frege’s ‘The Foundations of Arithmetic’. On this view, true descriptions represent a pre-discursive reality, such that sentences (e.g. Newton’s) are not just more useful than other sentences (e.g. Aristotle’s) but are more useful because they correspond to How The World Really Is.

This is often referred to as the correspondence theory. The correspondence theory of mind and language maintains that our mental constructs and sensory impressions are linked to real, external objects and phenomena that exist independently of human thought and social engagement. These objects and conditions remain constant, regardless of whether humans are aware of them or even if humanity exists. For example, our concept of “fruit” aligns with a biological classification of certain types of edible plants. This classification exists outside of any human-generated criteria for differentiating fruits from, say, vegetables or grains. In the same way, according to the correspondence theory of language, our words point to actual objects, and our sentences aim to describe states of affairs. A sentence is considered false if it doesn’t accurately represent the way things are, and true if it does. This means that the structure of the world exists independently of human language.

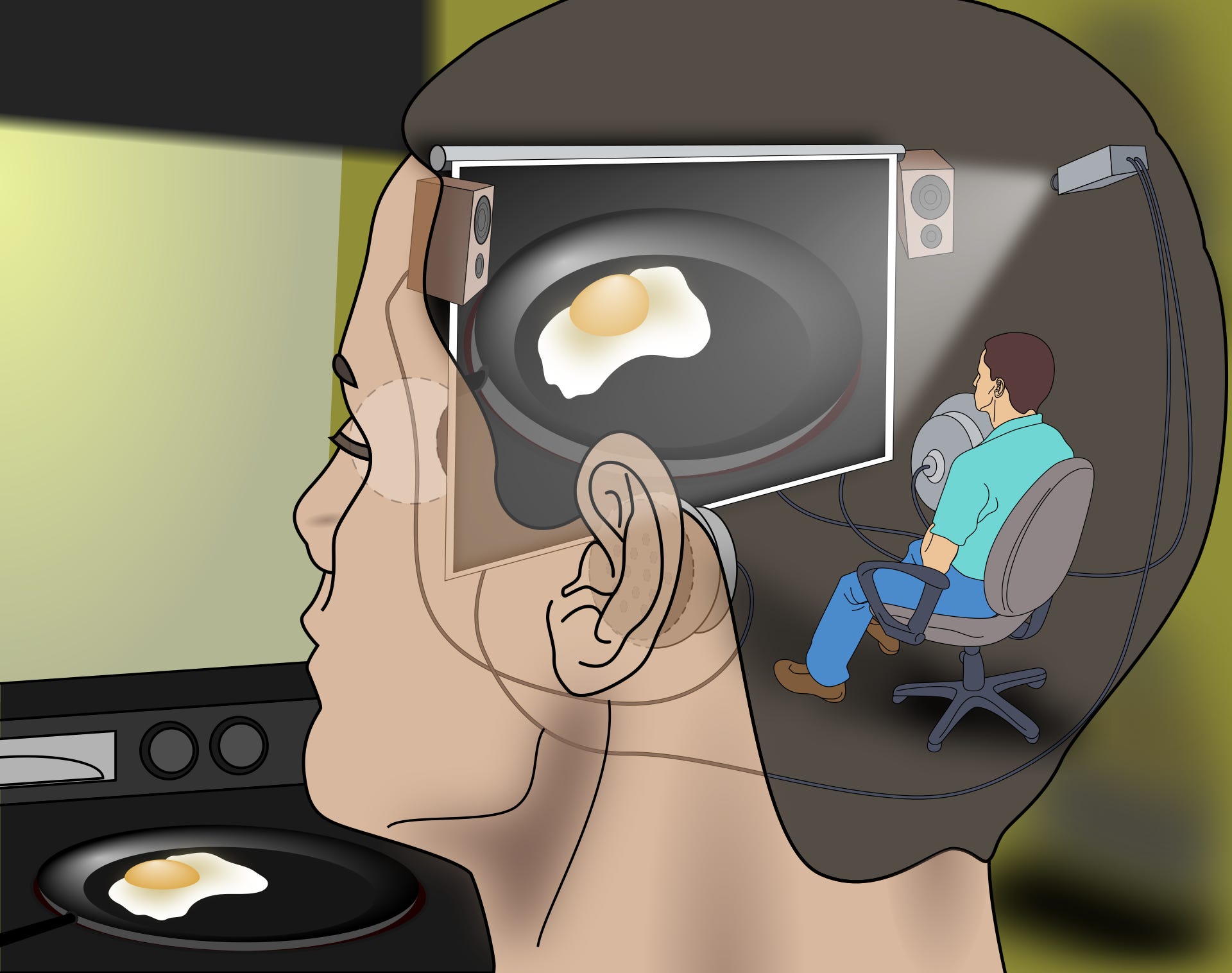

Put this way, language is taken to mirrors the intrinsic structure of reality rather than being a tool for coping with it. Words act as pointers to a mental or linguistic representation, something which philosophers might call a ‘proposition’, like a picture referred to by words. And these mental/linguistic entities are taken to correspond to something that, as it were, looms behind such things, something called ‘Reality’. So when I say “this chair in front of me”, this is taken to mean that I have a mental image/proposition about it (as opposed to me simply using signs to communicate some intention I have, and trust that, because of our shared socialisation, my interlocutor interprets the signs as I intended). And this mental image I am referring to, in turn, is taken to represent the nature of reality.

Historically, we have looked for something eternal, transhistoric, above and beyond human social activity, as the arbiter and measure of discriminating true sentences from false ones; Nature, Reality, God, Truth. This representationalism is the backbone of the western intellectual tradition. It manifests in the sciences, such as neuroscience’s portrayal of the mind as a Cartesian theatre where human cognition is an ahistorical, non-linguistic, non-social computational system “representing” environmental features. But most of all, it is the saving grace of analytic philosophy and what keeps philosophers in business.

This tradition historically held that the aim of enquiry is to represent what lays outside the human mind, be they Platonic Forms or the Will of God or the arrangement of atoms in the void. Its corollary is buckets of ink spilled on armchair philosophising about the ‘true’ and intrinsic nature of ‘p’, to which the average layperson is supposedly confused about. Much of analytic philosophy is parasitic on this representationalists tradition (notable in the Myth of the Given and the correspondence theory of truth), for if we forego it we will no longer be interested in asking bad questions that aim at ‘getting reality right’.

I will not delve into the full objections to representationalism here, as I have done so from a Pragmatist perspective in another post. I will only instead only discuss its implication on how we view the meaning of words, particularly with respect to gender.

Language as Representation

Philosophers often link meaning and truth together by taking a ‘truth-conditional semantics’ approach to meaning, where the meaning of a word is equivalent to its truth conditions - the circumstances or states of affairs under which it would be true. So in order to understand ‘the cat is on the mat’ requires knowing under which circumstances such a sentence would be true, that is, when there is a cat and a mat, and the cat is located on the mat. Accordingly, the meaning of a sentence, which results from the meanings of its component words and their arrangement, determines its truth conditions. The use and context (what is called ‘pragmatics’) of the sentence are usually - though not always - taken to be irrelevant and rarely factor in within the analysis; what matters most is the ‘semantic content’ of the sentence being communicated, which is the meaning of words in isolation from their use in real-world situations (pragmatics). ‘Semantic content’ is viewed in the form of “propositions” - the concepts or ideas that sentences express, which define their truth conditions.

For the representationalist branch of philosophy—which encompasses by far the majority of philosophers—the meaning of a sentence determines the conditions for it to be true, and these conditions are ‘when a word or sentence corresponds to reality’, so that ‘meaning’, ‘truth’ and ‘correspondence to reality’ come to be more or less interchangeable. Here, words are taken to directly correspond to pre-existing categories in the world, so that the job of language is to accurately represent those entities or categories.

Thus, it is unsurprising that when applying this view to the contemporary gender debate on the meaning of the word ‘woman’, it is taken to have a fixed meaning based on observable criteria. It has been held, for instance, by those against reforming this part of our language, though usually implicitly, that the truth of sentences containing the word ‘woman’ depends on necessary and sufficient criteria, typically including some notion of biological features such as having XX chromosomes or gametes. Essentialism provides the “fixed categories” that representationalism seeks to describe, while representationalism offers a philosophical justification for the essentialist views. When confronted, essentialists will thump their fists on the table and assert that we are beholden to a non-human entity called ‘Reality’ which their descriptions accurately represent, and it is on this basis alone that we should act.

This view of language, which posits a direct and unmediated link between words and reality, is precisely what Thomas Kuhn once parodied, saying that it is as if there is an independent Reality that has its own language, and when we utter a sentence and it is ‘true’, then it has been correctly picked out from within Reality’s language. However, if become Wittgensteineins and start seeing language as a tool rather than a representation of reality where each word has a direct, pre-existing counterpart in reality, and in which there is an isomorphic relationship between them, we will stop looking for “necessary conditions” for the possibility of language representation. Instead, we will understand the meaning of words in terms of their function, and acknowledge that they are descriptively determined by their usage among the linguistic communities in which they appear (more on this Wittgensteinian theory of language later on).

Gender Essentialism

Unfortunately, however, this general mode of reasoning where words that figure in sentences are held to correspond to or represent ‘Reality’ often implicitly bleeds over from philosophy departments (which Paul Feyerabend once rightly described as “the witches’ brew, containing some rather deadly ingredients”) into cultural politics. This has been most recently exemplified by the ‘what is a woman?’ debate popularised by right-wing reactionaries such as Matt Walsh and Ben Shapiro and ‘gender critical’ feminists such as J. K. Rowling and Germaine Greer.

These figures are gender essentialists. Gender essentialists typically hold that certain properties or traits are necessary and sufficient for determining one’s gender. From this perspective, one’s biological sex (typically defined by traits such as reproductive organs, gametes, chromosomes, or secondary sexual characteristics) is seen as both a necessary and sufficient condition for being a man or woman. In the case of “woman”, an essentialist view might hold that having XX chromosomes, female reproductive organs, egg cells, are necessary conditions. This means that to be a woman, one must have these biological markers. If someone does not have these biological markers, they could not be classified as a woman. These markers would also count as sufficient condition; that is to say, they would be enough to classify someone as a woman. Put together, having these criteria (for example: XX chromosomes/female reproductive organs/egg cells) are both necessary and sufficient conditions to the meaning of the term ‘woman’ to obtain.

Today’s anti-language reform conservatives justify this essentialism by reference to ‘how things anyway are’—what a woman is just is that way! And the radical feminists typically justify essentialism by reference to sex-specific political considerations (such as protecting “real” women), while then ironically overlooking that discrimination against women is not on the whole accounted for by biology (even though biological markers are statistically relevant) but rather by social structures and schemas like gender expressions.

Why Gender Essentialism Fails on its own Terms

However—if we really wanted to indulge the representationalist view on its own terms about meaning and reference—any essentialist definition of the terms man and women nevertheless ultimately fails.

Essentialism is committed to an outmoded platonic reality/appearance dualism: a distinction between the world of “Forms” (or “Ideas”) and the material world that we perceive through our senses. The Forms, according to Platonists, are perfect, eternal, and unchanging, and they represent the ‘true’ reality. The material world, on the other hand, is a realm of appearances—imperfect and ever-changing copies of the Forms. When this was taken up by the the Nazis (to jump to a more crude application), it was thought that one can appear human in all respects, but merely looking human is not enough to make someone human—there is something deeper that’s inside them, an inner human ‘essence’ within which the physical body might belie to the naked eye. The Nazis of course thought that Jews did not have this human essence, this necessary and sufficient condition for the meaning of the word ‘human’ to obtain when applied to such beings.

This dualism underlies the whole idea behind racial ‘passing’; though a multi-racial person might pass as white, race essentialists would maintain that they aren’t really white (according to the rules of their racial taxonomy). Appearance and behaviour alone does not make someone a member of a category—it is something deeper that does, an essence. While fool’s gold might look like gold, it is an entirely different chemical; and this type of essentialising we do in the sciences works the same way for kinds of humans—we think of some kinds as natural and others as invented, ‘merely’ social.

We can do this for any category we like. What makes a cat a cat is an inner cat essence, and this essence determines cat traits; having claws, being lazy, meowing, having four legs etc. This essence moreover dictates how a cat ought to be; any deviations from these traits (there are cats who don’t have four legs, aren’t lazy etc.) are abnormal (and even bad because the essence is not fully manifested in appearance). And lastly, the essence of the cat (or any thing) is unchangeable; once a cat always a cat.

So likewise, what makes a woman a woman, the essentialists argue, is an inner ‘womannes’—a woman essence, and once a woman always a woman. As noted, sex and gender essentialists’ definition of ‘adult human female’ usually maintain that sex chromosomes/sex organs/egg cells are this essence, just as the essence of gold is element number 79.

But this only moves the line of enquiry one step back, as the the traits listed by gender essentialists as being necessary and sufficient, are not always, in fact, necessary and sufficient. Sex chromosomes do not only come in xx and xy, and male and female phenotypes do not always correlate with those sex chromosomes. Any essentialist definition of man and woman would thus invariably be contested by counter examples, such as intersex individuals (who make up 2% of the population), individuals with androgen insensitivity syndrome, individuals with mixed genitals, and so forth.

Defining sex—as in the word ‘female’ in the definition of the word ‘gender’ as ‘adult human female’—based on certain characteristics, like genitals or chromosomes, over other characteristics is, in the end, a social decision. For example, the people in the image above have Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome. They are genetically XY (typically classified as “male”), but their body doesn’t respond to androgens, resulting in physical characteristics that are typically classified as “female.” Yet, society tends to classify such individuals as female, based on practical considerations such as morphology/physical appearance, despite their XY chromosomes.

If you want to see how the essentialist games really fails try and define the word ‘chair’ in essentialist terms. You can try and insist on some set of essential features for the word ‘chair’ that excludes it from ‘sofa’ ‘couch’ ‘stool’ ‘recliner’ and so on (or for the word ‘mug’ that distinguishes it from ‘cup’, or for the word ‘sandwich’ that distinguishes it from ‘burger’), but there will always be some chairs that fall outside those necessary and sufficient conditions. The meaning of ‘chair’, just as ‘cat’ and ‘woman’, is therefore determined in use. That is to say, the term ‘woman’, just like ‘chair’, may have some common “family” resemblances, but no subset of these resemblances can be minimally definitive.

Another issue with essentialism with respect to gender is that hardly anyone knows what their sex chromosomes are. A chromosome based definition is one that no one can actually use in practice; we don’t carry a test to determine people’s—or our own—chromosomes before gendering someone. On the essentialist sex-based theory of gender, people would then not know who is or isn’t a woman or a man (yikes!).

Nor does the theory capture our ordinary use of the term ‘woman’ and ‘man’ when classifying someone in practice. It would suggest that an intersex individual who was assigned female at birth, has female genitalia and female sex characteristics but has XY chromosomes and no uterus is not a ‘woman’. But, descriptively, most competent users of the term ‘woman’ would reject this, as they in fact do. It would also suggest that a trans person who has sex reassignment treatments, and so has most of the traits associated with the biological makers associated with the category ‘female’, is not a ‘woman’. Again, descriptively, competent users of the term often (even if unwittingly) use that designation. And at any rate, normatively speaking, it seems like we would want an intersex and trans inclusive understanding of the term. In short, the essentialist theory of gender seems to not fair very well in terms of theoretical virtue in capturing ordinary usage.

What we tend to do in practice is classify people based on family resemblances of the clusters of features that seem to coincide with gender expression:

Walking down the street, and we come across the humans in the image above. Most people will almost always identify the person on the left as ‘woman’ and the person on the right as ‘man’, despite their chromosomal make-up and gametes (both individuals are in fact transgender). That’s because we tend to go by pragmatic considerations such as morphology.

At any rate, descriptive accounts these (though often important because they sometimes give us pragmatic accounts of why we do something) should not be the final arbiter on how to carve our concepts: our main concern about ‘what is X?’ must take into account our normative considerations, such as whatever seems to make more people happier and less people unhappier.

Against Representation: All Enquiries are Pragmatic, Normative and Social

Ameliorative Approaches to Gender Categorisations

The premise behind the question ‘what is a woman’, as it is typically proffered, is an erroneous one. If we were actually interested in the meaning of a word, we would approach lexicographers and ask: ‘how is the term ‘women’ used in our ordinary language?’ The answer would probably be very uninteresting, something along the lines of: ‘currently the term seems to be context-sensitive, some linguistic communities seem to assign the term ‘woman’ to people who perform given social roles to a certain level, and at other contexts the term seems to refer to certain individuals which have similar clusters of biological markers, and at other contexts it refers to a gender-identity with which individuals sincerely self-identify and express themselves by’. Once we are given such an answer (which is at any rate descriptive), we could, more interestingly, also follow that by a revisionary normative question posed among ourselves: ‘should we retain that use, or is there a better one?’. The latter is the position of language reform advocates with respect to gender.

This reform is a kind of conceptual engineering that feminist philosopher Sally Haslanger calls an ‘ameliorative project’, that is, an analytical . . . project that seeks to identify what legitimate purposes we might have (if any) in categorizing people on the basis of race or gender, and to develop concepts that would help us achieve these ends. I believe that we should adopt a constructionist account not because it provides an analysis of our ordinary discourse, but because it offers numerous political and theoretical advantages.

Intrinsic to Haslanger’s way of thinking is that, following Wittgenstein, language is a tool to help us achieve our ends and not a medium for representing reality.

Yet, what we get in popular conservative discourses is a nonsensical question underpinned by representationalist assumptions which asks: ‘what is a woman, really’ i.e. what is the essence of gender, or how does the word ‘woman’ correspond to the intrinsic nature of the world?

This question slides down the confused and misleading representationlist bent towards meaning by framing the transgender issue as a subject of metaphysical investigation concerned with getting at the ‘true’ essence of ‘womenhood/manhood’, rather than what it actually is in practice: a normative debate on how we ought to carve out our concepts related to gender. The question in the latter sense is therefore not ‘is there really such a thing as p gender/sex/race/caste/sexuality’ but ‘how should we talk about p gender/sex/race/caste/sexuality, if at all?’.

We are the Arbiters of Classifications Categories are there for us, not us for them. We somehow forget that we are the arbiters of classifications and denotations, and that any analysis bottoms out on socio-cultural considerations. Even in the sciences, demarcating species in biology or talk about neutrons in physics are, in the final analysis, sociocultural issues that we agree upon based on consensus.

It was social consensus, for instance, that determined whether all swans should be white even after we later found their equivalent black ones or whether those black ones in Australia should also be considered swans despite their difference in colour; there was no fact of the matter on what the term ‘swan’ denotes other than our social agreement on how to carve it. Our consensus on the latter description does not mean that, after the fact, we can now say “it was chosen because it corresponds to how the world is”. It did not. The classificatory scheme was carved by human beings.

The mistake is to think that there are stand-alone, pre-theoretical Truths that are divorced from socio-cultural concerns. This is happens for instance when some people assert that “p is an ineluctable biological fact!” and consider that to be the be-all and end-all of what ought be done, when it is—whether rightly or wrongly—a way to justify antecedent social and linguistic practices.

So the question isn’t ‘are trans women women?’ just as much as it isn’t ‘is there such a thing as a black swan’ or ‘is there such a thing as neutrons’ or ‘is there such a thing as noble blood (i.e., a correlation between skin colour and IQ)’ or ‘is there such a thing as human nature?’; rather, the question is always ‘how should we talk about these concepts, if at all?’. Any question about whether p exists or what should we include within the category p has to be made in reference to our socio-political and normative goals.1 This point is missed when we adhere to the myth of an absolute fact-value distinction which representationalism affirms, or that the way we categorise, classify and describe things—from the sciences to culture and ethics—is to ‘represent reality’.

It is true that we often establish rigid criteria and boundaries for ‘scientific’ categories. But we only do so because it serves our normatively desirable interests for predicting and controlling. Even within such rigidness and essentialism, the descriptions adopted in the sciences are idealisations, conceptualised for making models more tractable. Most of these models, moreover, eventually outlive their usefulness—and the phenomena being described and categorised are themselves literally created where they did not previously exist (after all that’s the main task behind experiments) and often stop existing altogether, like phlogiston and the luminiferous ether (see Hacking 1983, ch. 16). But the point here is that essentialism, where certain universal and inherent characteristics define specific categories, has been wonderful for making predictions and generalisations (for why this does not, still, carry metaphysical implications, see my other post) but we have mistaken the usefulness of essentialist language in scientific modelling for the aim of predicting, for the idea that such language must apply to all other cultural domains.

Similarly, the binary conception of sex tied to biological markers in the population is a classificatory scheme that humans have usefully developed and applied for human medical practices, often even projecting onto the animal kingdom. But the model, like all models, is a pragmatic and idealised constructs that help us simplify and manage complexity, and is often forced to admit variability (as in the case of intersex and other conditions). For instance, though many species do reproduce sexually with “male” and “female” roles, there is significant diversity in the animal kingdom in terms of how these roles are defined and carried out. Many bird species have ZW sex-determination systems, where it’s the females that can be either ZZ or ZW, and males are always ZZ, which is the opposite of the XY system in mammals. Some reptiles, like some species of turtles and crocodiles, have temperature-dependent sex determination where the sex of an individual is determined by the temperature at which the eggs are incubated, not by chromosomes. Some fish and amphibians can change their sex during their lifespan. There are also numerous examples of animals that don’t fit neatly into binary male/female categories, such as hermaphroditic species which have both male and female reproductive organs. So while a binary understanding of sex tied to biological markers might be useful in some contexts (such as human medical practices), the understanding is not an isomorphic representation to properties in the world.

This applies not just to the classification of sex and gender, but to any system of categorisation we use—be it related to biological taxonomy, sociological demographics, linguistic semantics, or any other field; they are tools for our (social) goals. Them being tools, of course, doesn’t imply that “anything goes”, some categories are better than other ones for the purposes of carrying out specific goals. A hammer is better than a toothpick if our goal is to hit a nail. But because talking in some way about the existence of atoms or the existence of human categories is better than some other ways for the purposes of a given field, does not make those ways isomorphic representations. And it does not preclude the possibility of different ways of talking to be more suited in different fields.

When we take off our lab coats, and we come across a piece of gold-like substance or a swan-like being or a woman-looking person, we do not think of necessary and sufficient conditions (essences) and ask: ‘does this chemical substance have an atomic number of 79 and an atomic weight of 196.967?’, or ‘can this being produce fertile offspring with swans?’ or ‘does this person have egg cells?’. We don’t stop and go about testing the substance using an X-ray spectroscopy or inseminating the swan-like being with swan semen (which is, anyway, only one way of defining ‘species’ that is itself contested by other ways) or checking the chromosomes of the woman-like person. Rather, we classify such things through “family resemblances” of our over-lapping linguistic practices. In other words, ordinary speech—say, about vegetables, fruits, bovines, whales, women, chairs, cats, swans, gold etc., are not always co-extensional with their scientific counterparts. It’s pragmatism and normativity all the way up and down with respect to our classificatory schemes; pragmatic and normative social consideration, whether in the sciences or in ordinary speech, have primacy over ontology.

A Wittgensteinian Approach to Gender

Use-conditional approach to Language

Let’s turn to how Wittgenstein would have replied to gender essentialists. Providing definitions for words like ‘woman’, as Mr Walsh and Co. are demanding of us, is something that we rarely have to do outside of technical contexts because theres rarely any pragmatic point in doing so (for example, where we offer stipulative definition for the purposes of an academic paper or an operational definition for the purposes of conducting an experiment). We almost always don’t need definitions for our terms, all we need to know is how to use them in ordinary language. Wittgenstein argues this in his Philosophical Investigations when he writes: “I use the name ‘N’ without a fixed meaning. (But that detracts as little from its usefulness, as it detracts from that of a table that it stands on four legs instead of three and so sometimes wobbles)”. Thats because the primary function of language is to facilitate communication and convey intentions, and if that can be done, then demanding essentialist definitions is superfluous.

To see this more clearly, we shall examine how Wittgenstein analyses the way we form concepts and meanings. First he starts by saying that the rules that govern the use of our language (what he calls “grammar”) do not make themselves up based on a set of independent ‘structures of reality’, on some essences over and above the rules. Rather, he says, the rules are constituted by themselves. That is, meanings and concepts are created by our linguistic practices; by the routines, habits and rules of language usage. The mere encounter with a “horse”, for instance, does not give us the concept “horse”; experience does not, in itself, determine how we carve out our concepts or how we categorise objects. Or in other words, the usage of a concept is not absorbed from an independent object, nor does it come from the mere similarity between a bunch of objects (and nor is there always similarities between objects that fall under the same concept!). And so, there must be something creative, active and dynamic in concept formation, and there must be something over and above the object being referred to. This, to Wittgenstein, is the users of a language and their linguistic practices; the way language users use different symbols to communicate intentions.

From this understanding of rules of language grammar, Wittgenstein takes the meaning of words to be coextensive with their use. And use is a rule-governed activity; it’s reality is created by human practices. Collectively, we agree on using this word in that way, and that rule is created by us giving it that force (think of rules for etiquette or rules of rights, rituals, laws and games). The act of reference to a rule constitutes its reality just like the act of reference to a ‘right’ or a ‘law’ constitutes its reality. There is no reality to rules other than people following them, just like a game is something people create merely by playing it. Wittgenstein uses the latter metaphor in describing what he calls ‘language games’; the rules of a game compel players to act in certain ways other than certain other ways, but this compulsion does not exist outside of the practice of following the rule. There is no logical or physical necessity to rule following, players can choose to break the rules of a game at any point. It’s just that, as rule-followers, players collectively impose sanctions on rule-breakers; there isn’t some external entity forcing the players to use a specific rule. And similarly, the corollary is that our linguistic practices do not ‘represent’ or ‘correspond’ to reality, but they rather constitute it. When people appeal to a “reality” to which a word corresponds to, what they are in fact doing is appealing to an implicit intersubjective standard of rule-following, where that reality is just a bunch of other people’s habituated readiness to make a similar appeal to a rule and act on it.

Language is a Tool

It happens that the rules of our language games tend to be shaped by reference to how expedient they are with coping with our environment, coping with external causal pressures. Such pressures often force us to adopt conditional rules as heuristics such as ‘if we want X, we should follow Y rule’; but the way we talk about those causal pressures is ultimately a matter of human convention and agreement. And so in this sense, langauge is a tool for coping rather than a medium of representing.

Philosopher Donald Davidson offers a hypothetical to demonstrate this point:

Suppose you stumble upon a native of an isolated community whose language is radically different to your own. Alien to each other, you begin forming theories about one another’s behaviours. A successful theory is one where you could generate expectations of the native’s future behaviours, about what she will do next so that you are not taken by surprise, and vice-versa. Successful communication is thus one where you are able to make predictions about the noises and marks the native makes and those predictions end up coinciding with her own, and vice-versa. It is clear in this situation that the use of language is one of coping with another language-user, coping with another causal pressure, and not in “representing reality”. And so Davidson concludes that all ‘two people need, if they are to understand one another through speech, is the ability to converge on passing theories from utterance to utterance’.

Sometimes it may helps to think of language as we do numbers, since numbers invariably elude essentialist definitions. We talk about the number five all the time, but if someone asks ‘but what does the number ‘five’ really mean, what is its essence?’ we would be left baffled. In answering this, all we can do is come up with relational descriptions; the sum of two and three; one more than four, half of ten, the subtraction of 15996544524568 and 15996544524564 and so on, but none of these descriptions come closer to the intrinsic nature of ‘fiveness’. To be sure, these descriptions are all in some sense related to one another in criss-crossing ways in that they all make use of the word ‘five’. But if we want to understand the meaning of ‘five’, we have to examine its use in language—and use is a rule-governed activity; usage cannot be “read off” an object. Thus, numbers are part of a language game that function as rules; someone tells me to go buy five apples, I go to the shop and find the section marked ‘apples’ and count to five, with each number I pick up an apple. The word ‘five’ in this sense did not stand in for an object or represent it, but rather it simply functioned as a rule in a game. The point is that rules (no matter how much consensus they garner or how much we have mastered them through generations) do no more than govern how people ought to use marks and noises.

In this sense, we English speakers can talk about bulls using the signifier ‘bull’, but we almost never need to define what the word ‘bull’ is, and most people would call castrated bovines ‘bulls’ even though the technical name in farming is ‘steers’—but it usually gets the point across. Likewise, children can name ten animals but when asked for specific definitions, they will be baffled.

I talk about computers all the time, but if someone stops me and says ‘wait, can you provide me a definition of the word ‘computer’ before you proceed’, I wouldn’t have an immediate ready answer at hand. But, with Wittgenstein, I will wonder what the point of asking this was, and think, in Wittgenstein’s words: “Why do you put it so oddly?”. Is she questioning my grasp of the English language, my competence with technology? What does she want to be reassured of, exactly? If she responds ‘I just wanted to make sure you knew how sentences in which the word ‘computer’ figures correspond to Reality in a non-contextualised way’ or ‘I just wanted to make sure you can specify necessary and sufficient conditions for the truth of the sentences in which the word ‘computer’ figures’, I will be baffled. What would it mean to utter a sentence that is divorced from context and its conditions does not correspond to reality? This is all to say that terms don’t need to be complicated; if they are clear enough for a specific use or practice, then they are “correct”, and providing definitions for such terms then becomes a redundant task.

To provide a last example, the use of the word ‘gold’ as referencing a chemical substance with an atomic number of 79 and an atomic weight of 196.967 would only matter when we want to use that substance in that way. We did not agree to carve the meanings of substances with atomic numbers of 79 and substances with atomic numbers of 47 (silver) differently out of hot air, there was a pragmatic reason for doing so. For most of our history this has usually been to regulate trade and exchange. But when a layperson who knows nothing about chemistry and physics points to a yellowy-brownish, bright, shiny, metally thing which has an atomic number of 78 instead of 79 and says “it is gold”, that meaning is not ‘incorrect’. (Again: meaning is language-in-use, the word ‘cow’ does not literally mean ‘cow’ and we often use that word to designate anything that is ‘cow-shaped’ even though the technical definition is a female bovine that has bred). So she is simply using the word gold as a family resemblance, and not the rigid and essentialist designators used in chemistry (which themselves often admit variability and are often replaced altogether by new descriptions).

All meaning is ultimately guided by our social practices and norms; there is no domain of enquiry that operates from an Archimedean point from which to arbitrate the ‘correct’ meaning of a term. The norms that guide the meanings of terms in biology and physics may not be suitable for guiding the meaning of terms in carpentry, literature, ethics and art—even if there are many overlapping standards.

What we gather from Wittgenstein is that the final analysis of the ‘what is a women?’ question is in the end a reference to our pragmatic and normative goals: ‘how should we talk about gender and sex, if at all?’. In our current society, if our goal is to reduce the number of human suffering, then we should probably move away from a completely sex-based understanding of gender and admit variability in what the terms ‘man’ and ‘women’ denote, and accordingly change our linguistic practices towards intersex and trans inclusive understandings of the terms.2 What follows is that statements like ‘I am a woman’ are not understood as communicating something about the speaker’s genitals, gametes or chromosomes but something context-sensitive (which would include, in at least some contexts, the avowal of the speaker’s gender expression).

In effect, this would be how we have always talked about ‘women’ and ‘men’ throughout human history, as people have grasped those concepts without ever having any knowledge about what gametes and chromosomes even are. Children, too, begin to grasp such concepts at a very young age, often before they have any comprehensive understanding of biological sex or sexual reproduction, meaning that our understanding of gender is not reducible to an understanding of differences in biological markers. Children learn about gender roles and norms not (just) through explicit instructions such as “a man is such and such and a woman is thus and so”, but rather implicitly through their observations of others. They see how people are treated differently based on perceived gender, and they internalise these lessons. They then begin to identify with a certain gender and internalise the norms associated with that gender long before they understand what gametes or sex parts are.

So, what may be useful references for the designator ‘sex’ in biological discourses, may not be so useful elsewhere, such as when treating someone as their preferred gender or using preferred pronouns, or getting people the affirmative medical care they need. Both the terms ‘gender’ in our ordinary discourse and the term ‘sex’ in scientific discourse are socially construed parts of our language, and the only disagreement between essentialists and anti-essentialists is about the sort of ways we want to use language—everything else is someone attempting to smuggle in their provincial normative goals and social practices into the definition, and then saying it is ineluctable because it represents the intrinsic nature of things. It does me well here to again quote Richard Rorty:

” It is often said, for example, that we should stop using the concepts of “race” and “caste,” stop dividing the human community up by genealogical descent. The idea is to lessen the chances that the question “who are his or her ancestors?” will be asked . . . This line of thinking is sometimes countered by saying “but there really are inherited differences — ancestry does matter.” The rejoinder is: there certainly are inheritable physical characteristics, but these do not, in themselves, correlate with any characteristics that could provide a good reason for breaking up a planned marriage, or voting for or against a candidate. We may need the notion of genetic transmission for medical purposes, but not for any other purposes. So instead of talking about different races, let us just talk about different genes . . . the question “is there such a thing?” and the question “should we talk about such a thing?” seem pretty well interchangeable.”

—James Henry Leuba

In other words, the rejoinder to “but there are biological markers between population clusters” is “there certainly are, but they do not, in themselves, map on to one’s gender identity, nor do they correlate with any characteristics that could provide a good reason to deny people affirmative gender treatment, respecting their pronouns, etc..” Biological markers (which anyway, are at best ambiguously mapped to gender and sex concepts) or any other descriptive claims about our current linguistic practices are not morally relevant.

Home

Home About

About Entries

Entries Chat

Chat Kool Webpages

Kool Webpages Guestbook

Guestbook Kool Books

Kool Books Truth Table

Truth Table Contact

Contact