In 18th-century Prussia, a new breed of agronomist gazed on the tangled old-growth forests and saw inefficiency. These woods were messy, layered with rotting logs, mossy undergrowth, and a riot of species—oaks, beeches, lichens, beetles, boars—all woven into a system opaque to bureaucrats. So they replaced it. The Wald became a grid: row after row of Norway spruce, spaced like soldiers, their value reduced to “timber yield per hectare.” The state rejoiced. For decades, profits soared, and the model was exported elsewhere by colonial powers. Then the storms came. Monocultures toppled. Pests devoured the brittle stands. By 1900, Prussia’s “scientific forestry” had degraded the soil and halved yields.

James C. Scott calls this legibility; the state’s compulsion to crush the world into grids, maps, and categories to make it governable. Legibility, he argues in Seeing Like a State, enables control, yes, but at the cost of erasing the complexity that makes systems resilient, humane, functional. The (social and ecological) world is too unwieldy in its raw form for administrative manipulation; it needs to be crunched and converted into digestible forms. Premodern states were blessedly ignorant. They lacked the tools to track shifting harvests, unmapped villages, or the fluid identities and dense anthropological details of their subjects. But modernity armed them with censuses, cadastral surveys, transportation, uniform languages, legal surnames, freehold tenures, scientific forestry, and all sorts of other administrative tools. Suddenly, everything could be measured, taxed, and optimized. The world became a spreadsheet.

To the modernizing administrator, history is merely a sequence of examples of less rational modes of being. This isn’t always, everywhere, inherently bad, and legibility projects often are well-intentioned to alleviate the human condition. It’s just what any centralized sort of system of power must do to carry out its logic of centralized governance. The problem is that state agents (the urban planners, revolutionary elites, technocrats, and so on) often dismiss local knowledge (metis) as backwardness and see complexity as a problem to solve, not a feature. Thus, in the case of Brasília, the modernist capital designed by Le Corbusier as a “machine for living,” zones were segregated: sleep here, work there, commerce in tidy sectors. But humans are not gears. Street vendors colonized the voids. Families repurposed sterile apartments into communal hubs. The city’s “chaotic vitality” subverted the blueprint, proving that legibility and livability are often enemies.

The 20th century’s worst disasters followed this script. Soviet collectivization replaced peasant metis—local knowledge of soil, weather, and crop rotations—with central plans. Famine ensued. Tanzanian forced villagization uprooted communities into grid-like settlements, ignoring kinship ties and farmland logic. Starvation again. In each case, a high-modernist ideology—faith in technical expertise, contempt for tradition—crashed against the rocks of reality.

Scott’s heroes are the ones who resist, not with protests, but by evading. Nomads, Roma travelers, serfs playing dumb during tax audits. Their survival hinges on staying illegible, staying ‘out of the archives,’ slipping through the grid. But he also champions positive alternatives: Indigenous fire management, agroecology, and Jane Jacobs’ “eyes on the street.”

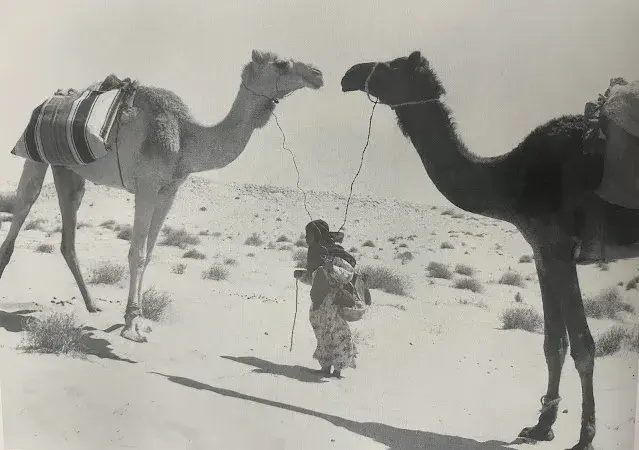

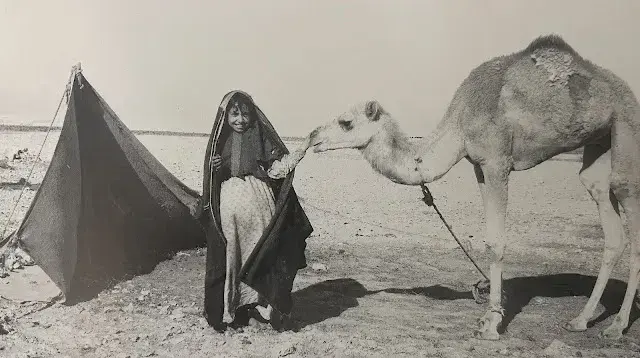

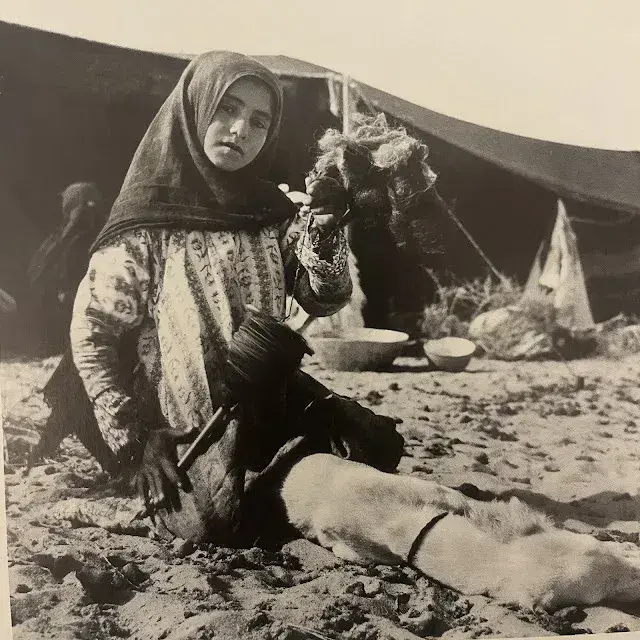

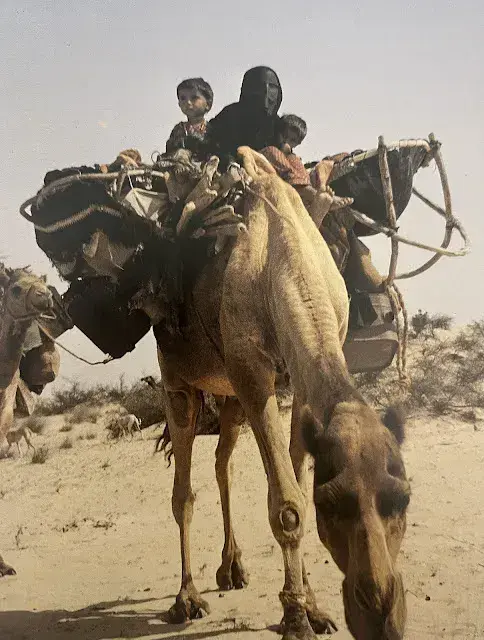

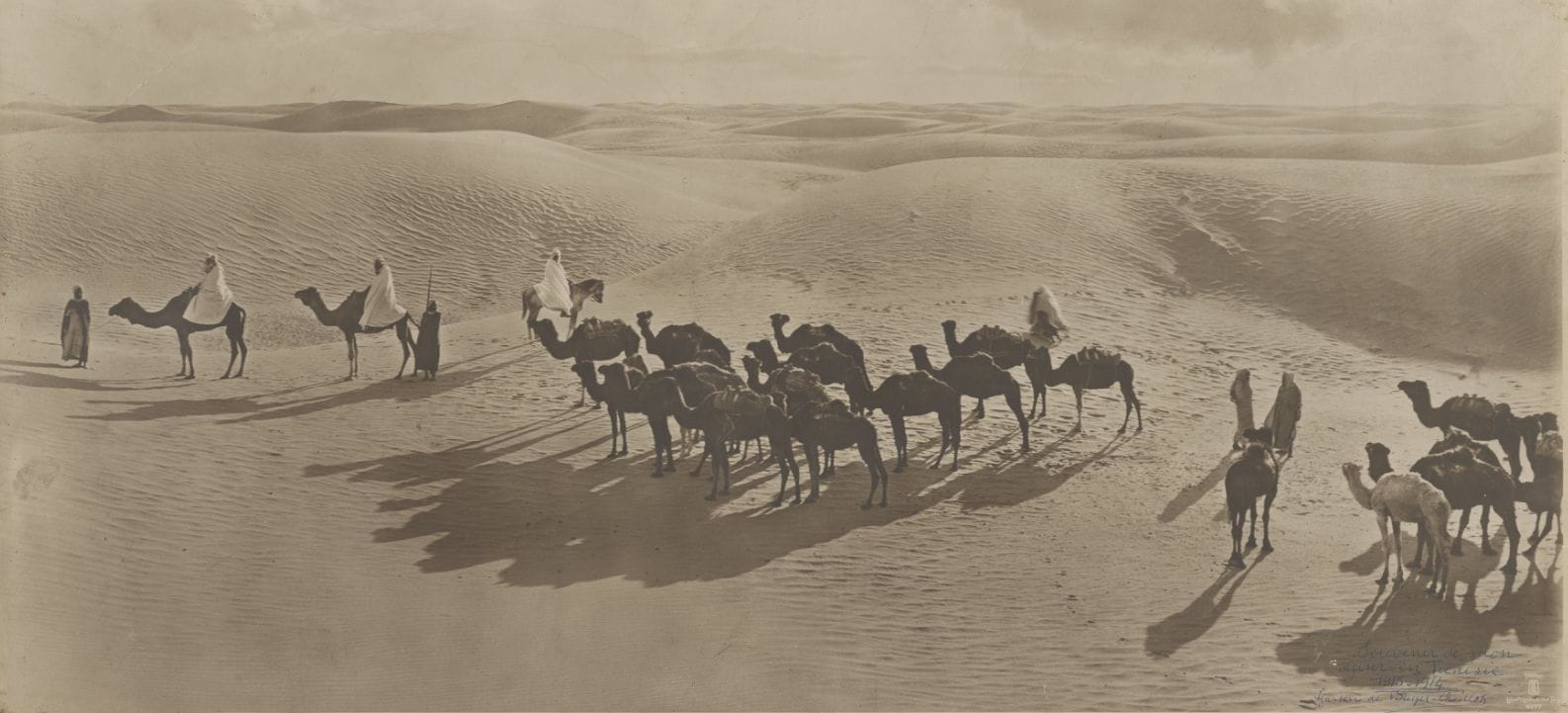

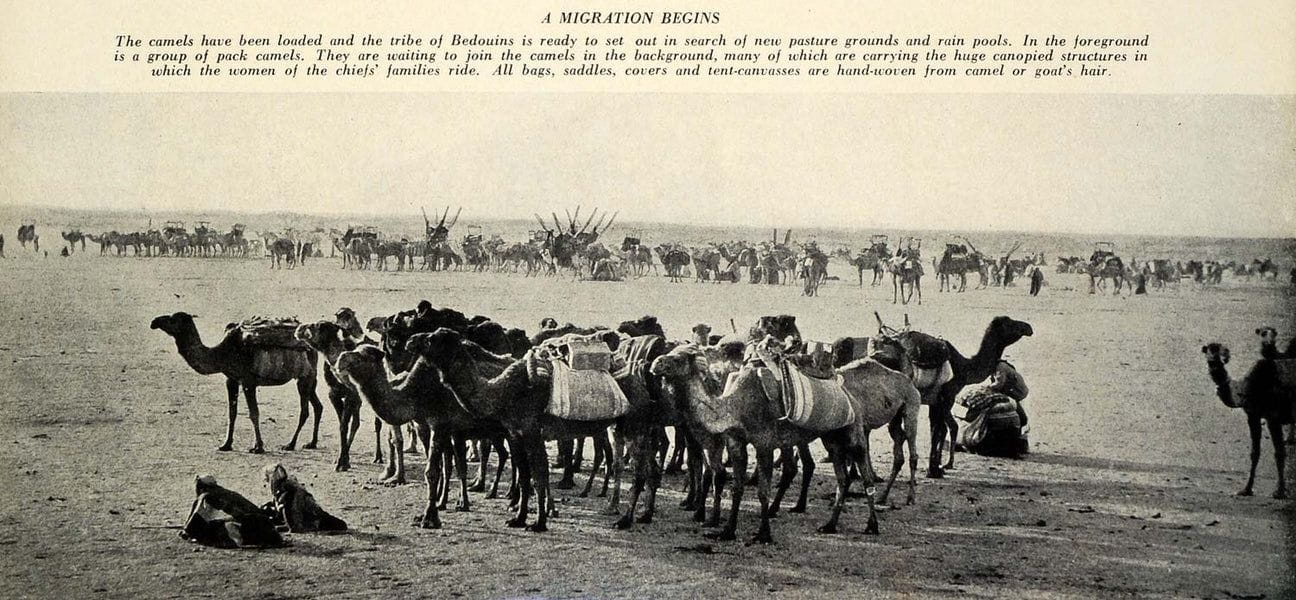

Arab nomadic pastoralists, scattered from North Africa to the Arabian Peninsula, have long embodied what James Scott might call the “illegible” par excellence: their social order, forged over millennia in spaces of hyper-aridity, rejected the fixities of territorial states. Organised into autonomous tribal units bound by a collective ethos of desert adaptation, Bedouin societies thrived on mobility, reciprocity, and finely tuned ecological knowledge. Their territories sprawled defiantly across modern frontiers; their seasonal migrations ignored the cartographic fictions of nation-states; their loyalties answered to tribal sheikhs, not tax collectors or land registries. For centuries they have evaded state administrations under various Caliphates and Ottoman empires, in a sense, having in Scott’s words “stayed out of the archives.” If you find them in the archives, this means something terribly wrong has taken place.

Postcolonial modernity, however, would declare war on this opacity. Emerging from the wreckage of colonial rule, mid-20th-century Middle Eastern states, obsessed with territorial consolidation and nationalist homogeneity, saw in the Bedouin active threats. Their cross-border movements muddied the fiction of sovereign control; their disregard for cadastral laws mocked the state’s claim to monopolise space; their tribal allegiances fractured the myth of a unified citizenry. As Cole (2003) notes, sedentarisation became the reflexive ‘solution’ to this perceived crisis: a High Modernist calculation to erase nomadic legacies and imprint state authority onto the desert. Beneath the veneer of humanitarian rhetoric of offering education, healthcare, and the ‘gift’ of permanent settlements lay a self-serving calculus. Land-use laws criminalised traditional migration routes; agricultural schemes replaced camel herds with cash crops; urban planning manuals recast pastoralists as taxpayers, conscripts, and legible subjects.

Yet these efforts of the early 20th century largely faltered. Sedentarisation programmes, whether framed as civilising missions or brute territorial grabs, underestimated the tenacity of Bedouin metis—the embodied knowledge of desert ecology, herd management, and social reciprocity honed over centuries. State-built settlements invariably collapsed under the weight of their own artifice, and pastoralists slipped back into the deserts. It was only with the advent of oil commodity capitalism that nomadic life was finally destroyed, in which industrialised agriculture devoured pasturelands, mechanised irrigation reengineered arid ecologies, and urban labour markets pulled Bedouins into wage economies. Essentially, it achieved what early state bureaucracies could not. But as Galaty and Salzman (1981) argue, capitalist modernity did not merely sedentarise the Bedouin; it dissolved the material and epistemic foundations of their world and replaced the desert’s fluid logic with the extractive grid of global markets.

With the reign of King Abdulaziz III and the intensification of the ‘national unification’ movement in the 1910s within Saudi Arabia, one of the largest sedentarisation projects ever seen in the Arabian Peninsula—perhaps in the world—was implemented. The primary objective was to dissipate tribal loyalties in favor of national ones, and an estimated 300,000–400,000 Bedouins were attempted to sedenterise in hundreds of subsidised ‘Bedouin villages’ known as ‘hijras’, after which they gradually began to pay alms tax (zakat) to the nascent state. Among Ibn Saud’s key strategies was to claim authority over all Bedouins who grazed seasonally in neighboring regions, insisting they were integral to the Wahhabi revivalist movement. This movement in turn drew on the ‘Ikhwan’ movement, a religious and military force of these sedenterised Bedouins, designed to solidify his rule in Najd and eventually became the central force in the military conquests that lasted from 1912 to 1930 to expand the third Saudi state from central Najd to Ottoman territories.

In his influential 1928 publication Modern History of Najd and Its Appendices, Amin Al-Rihani—much like Ibn Khaldun in the Muqaddimah—portrayed the Bedouins of Najd in condescending terms: polytheistic, untrustworthy, and disobedient. He argued that Ibn Saud’s initial difficulties in forging these tribes into a disciplined and ideologically cohesive army sprang from what he called the ‘Bedouin character’, shaped by a lack of permanent land or dwellings, making them resistant to the emerging Saudi state’s expectations of military discipline and uniform religious orthodoxy. According to Moner Nahedh, the first aspect of tackling this challenge involved “a policy of ideological intervention, based on converting the Bedouins to the Islamic principles of the Wahabi revivalist movement and persuading them to settle in agricultural communities.”

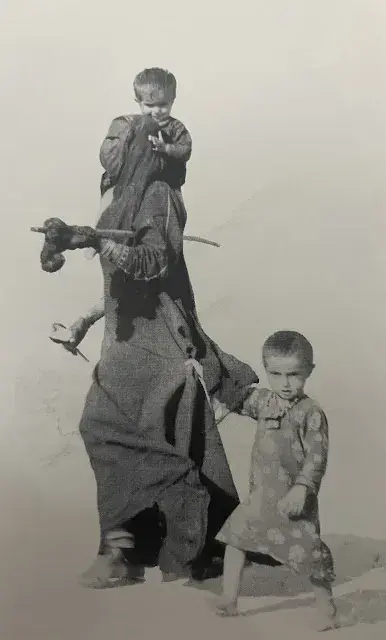

In doing so, ownership of herds and the autonomy of pastoralists had been severely curtailed; their freedom of movement and control over their herds, one being the product of the other, were steadily eroded in favor of the new state’s unification goals. Ibn Saud tackled this by instituting a massive sedentarisation program that combined civilisational and religious ambitions, effectively seeking to transform the Bedouins’ traditional, mobile pastoral existence into settled agricultural and urban lives. This was encapsulated in the push to move them, metaphorically and literally, “from tents of hair to homes built of mud and stone,” and to tether them to private property so, in Ibn Saud’s words, they could be “chained with the chains of ownership so we can benefit them, and if they sin, we can discipline them.” By binding their survival to the state—through dependency on the land, housing subsidies, the forced sale of camels, and other coercive measures—their longstanding self-reliance, rooted primarily in camel herding, was systematically dismantled. As a result, when the state found itself with the largest nomadic community in the world (by far the most numerous demographic within its borders) these newly settled populations struggled with the processes of modernity and remained largely unproductive. Bedouins generally held a culturally instituted prejudice against all kinds of agriculture, and this is found in various Bedouin poems.

Legally, the reforms extended toward abolishing tribal dirahs (collectively owned tribal land) and eventually, long after the dismantlement of the Ikhwan, culminated in the 1968 Public Land Distribution Ordinance, that is, giving the ruler’s or Imam’s right to allocate land as a form of patronage and reward for loyalty. The transition was also manifested in the shift from collective to private land ownership, with the tribe effectively losing its dirah and becoming client to the central authority, paying religious taxes to it.

There is a consensus in the literature on the failure of the sedenteristion projects of the Saudi state during the early 20th century, particularly that aimed at converting Bedouins into Ikhwan. The first measures of this began by sending mutawwa’ah (religious preachers) out to the deserts of Najd to guide the Bedouins toward sedentary agriculture, to obey Ibn Saud and the state’s laws, and to eradicate their traditional pastoral norms. There was in this a religious zeal of the Wahhabi orthodoxy in as much as realpolitik; Bedouins were since the dawn of Islam known to be very nonchalant in religious matters, still largely practicing polytheism and blending traditional pre-Islamic beliefs with Islam. By all measures, they were ‘heretical’ by the standards of the Wahhabi orthodoxy Ibn Saud was attempting to enforce.

The policy involved disaggregating larger tribes into specific clans, each assigned a plot of land with a well and financed dwellings, while compelling them to sell their camels, thus undermining the primary catalyst of their nomadic lifestyle. By 1920, numerous hijra (villages) had been established for the converted Bedouins (Ikhwan) of various tribes, complemented by changes in tribal leadership and the creation of encapsulated communities.

Now Ibn Saud had finally built this hyper-religious, ultra-zealous military force called the ‘Ikhwan’, began to adopt the distinctive white headbands (‘asāb’) which set them apart from others, and they were going to take back Al-Ahs and the Hejaz and were more than willing to go to war whenever the “waly amr” (or leader) called upon them. Having sold their camels, they were no longer autonomous and mobile, relying instead on wartime employment as Ikhwan soldiers. In peacetime, they became financially dependent on the state. This dependency relation coupled with their new acculturated religious fundamentalist attitudes made them in the eyes of the seeing state unproductive units. They turned their state-given settlements into mosques and did “nothing but pray” and shunned the state’s productive forces of agricultural labour, industry, and trade as heretical activities. In short, they became a massive drain on the state.

In response, Ibn Saud dispatched another wave of mutawwa’ah equipped with religious narratives about the righteous predecessors to underscore the virtue of productive labor, teaching that “agriculture, trade, and industry do not contradict religion, and that a wealthy believer is better than a poor one.” Moner Nahedh notes that such initiatives continued long after state formation, including the Wadi Sirhan (1950s) and Haradh (1960s) agricultural projects, both of which ultimately did not meet their intended goals.

An additional paradox of these reforms was that the deeply religious and militarized Bedouins, now priding themselves on sedentarism and Wahhabi orthodoxy, began attacking and killing other Bedouins labeled ‘infidels,’ thereby undermining the broader state-building enterprise. The state had created a new class of human beings through the tools of sedentarisation, religious indoctrination, and dependency and called them the Ikhwan. But once that classification was created, it had a life of its own. The category looped back on the state, and the people so defined by their hyper-orthodox identity destabilised the very project of state-building that had given rise to them in the first place. That’s a textbook example of what philosopher Ian Hacking called the ‘feedback loop’: once specific categories are applied to human beings, the categories don't stay static but “loops back” and shape both the people so named and the society that named them.

In 1919, Ibn Saud convened a conference in Riyadh with local leaders and religious scholars to address this radical zeal—an outcome of his own push for legibility—culminating in a Fatwa that decreed, among other things, that “the Bedouins are still Muslims” and that discrimination against migrants (Bedouins who had moved to settled areas) based on their origins was forbidden.

Nonetheless, the contradictions between the Ikhwan’s religious fervor and its function as a military and political tool of the central authority led to the movement’s final destruction and dispersal, hastened by raids into British-controlled Iraq and opposition to modern innovations such as radio, telegraph, and even tobacco. In 1927 and 1930 respectively, the Ikhwan started a crusade against the Saudi state itself but were no match to the modern weapons of the Saudi military backed by the British Empire and were quickly crushed. In the end, some were incorporated into the Saudi National Guards, but many reverted to their ancestral pastoral activities until the new promises of oil labour showed up. But the damage had already been done: the reduced productive capability of pastoral nomads after living a semi-nomadic life brought them into poverty as well. In consequence they have lost the social value that was granted to the Bedouin population, and the automobiles introduced that made camel transport non essential, as well as their monopoly on caravan routes had been dismantled.

anyway, this is why i'm an anarchist.